The text was previously published on the occasion of Jasmin Werner's exhibition Schloss der Republik Burj Khalifa OFW I, which was shown at Come Over Chez Malik's and hosted at the Deutsche Seemannsmission Hamburg-Altona.

Elena Malzew, Elisa Barrera, From Hamburg With Love

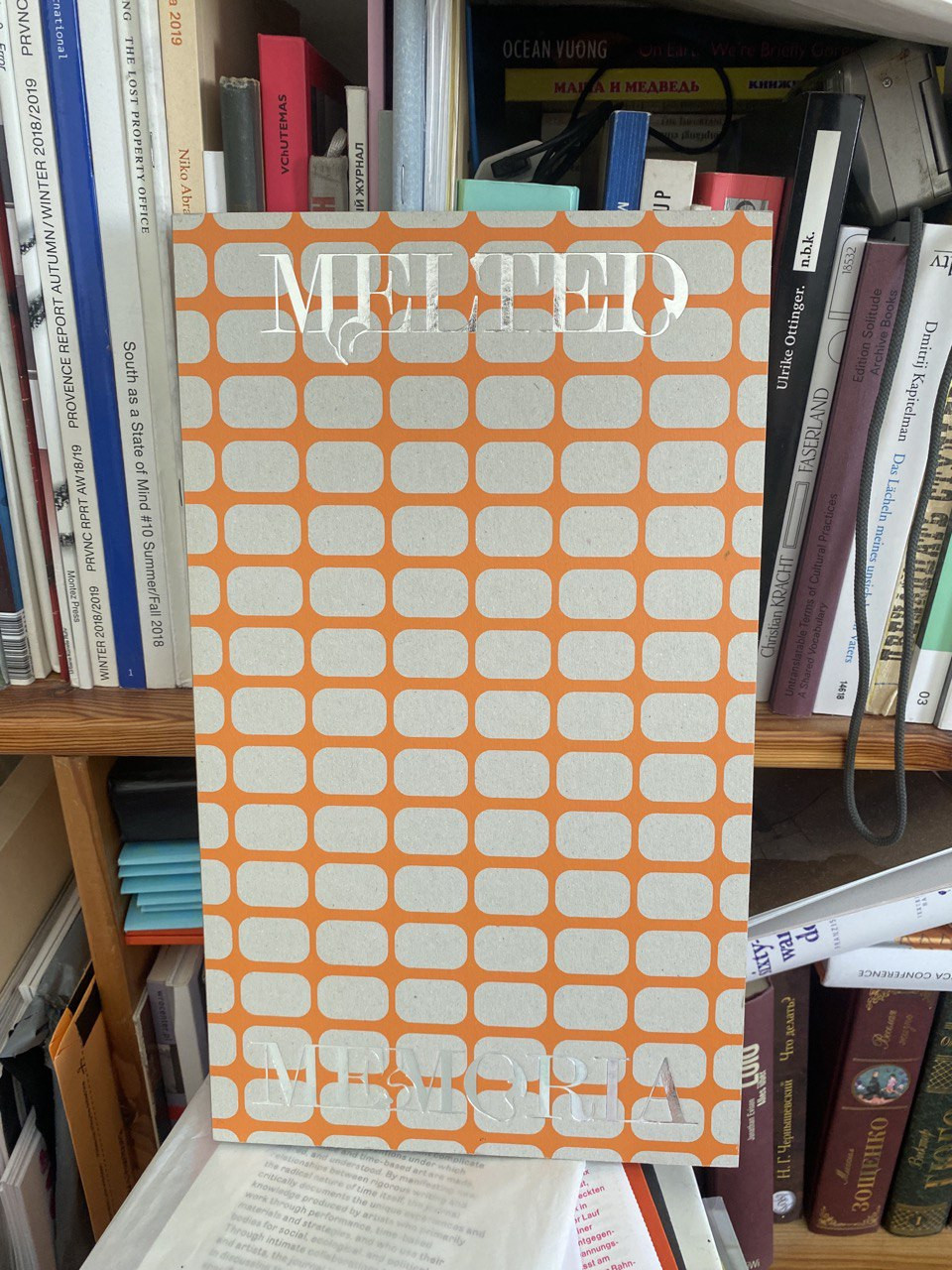

Jasmin Werner. Melted MemoriaWalther König, Cologne2020

Elena Malzew, Elisa Barrera

From Hamburg With Love

In her work Schloss der Republik Burj Khalifa OFW I, Werner combines images of architectural details of the Palace of the Republic and the newly built Stadtschloss Berlin, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, and private photographs by her cousin, Chris Cadawas, into a sculptural collage.

At first glance, these images are not necessarily related. However, through contextualization and upon closer inspection, they form a densely woven narration: we are introduced to a global history of knowledge and trade. In an attempt to give the reader a brief overview, we will sketch out some of the elements that come together in the sculpture.

The weaving of the individual strands came about after the demolition of Berlin’s Palace of the Republic, which was built during time of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Several tons of steel from the recycled steel beams of the symbolic building were sold to the United Arab Emirates, where they were used to build the gigantic Burj Khalifa. At 829.8 meters high, it is the world's tallest skyscraper, built from 2004 to 2009 and named after Emir of Abu Dhabi Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan. It houses private flats, offices, restaurants, a hotel, a variety of leisure and wellness facilities, and several radio and television stations. The last thread in the work is Cadawas, Werner's cousin, born in the Philippines and living in Dubai since 2013, like many Filipino migrant workers. There, she has worked in a men's hairdressing salon for several years. It was Chris who sent her cousin Jasmin the photographs of the salon, which Jasmin then processed into Schloss der Republik Burj Khalifa OFW I.

These different threads come together via global detours in Werner’s exhibition. They illustrate how the international economy, state histories, the global network of the world of work, and personal destinies are closely interwoven into a complex ecology and can hardly be considered separately.

Werner's central concern and interests lie in issues of labor migration, with a special focus on the Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW). Since the beginning of the twentieth century, these Filipino migrant workers have been identified as so-called “global citizens” who set out in search of work worldwide to earn money for themselves and their families. For several years, about 10 percent of the total Filipino population have been global migrant workers. Approximately four hundred thousand of the world's 1.6 million seafarers are Filipino. The sending of workers abroad is strongly advocated for and supported by the Philippine government. Financial institutions tailored to the needs of migrant workers have even been created to facilitate the flow of money from around the world back to the Philippines. In 2018, these overseas workers remitted about $6 billion back to their home country.1 Without their contributions, the Philippine economy would not be able to maintain its level: labor migration becomes a necessary resource in a globalized world economy.

A place where this network manifests itself locally is the Deutsche Seemannsmission Hamburg-Altona e.V. (German Seamen's Mission Hamburg-Altona), which has a history going back to 1901 and is tasked with providing accommodation, food, and a substitute home for seafarers—even if only for a short time. Here, global networks of labor—of which the Overseas Filipino Workers are a part—are condensed. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in February this year, many seafarers have been unable to return home due to legal regulations and are literally stranded at the Seamen's Mission. The physical and psychological strain of several months of isolation at sea has now been compounded by the strain of isolation during the pandemic on land. The seamen’s mission is located at the river Elbe and surrounded by luxury designer boutiques and offices. In the midst of the gentrification of the port area, in the dining room of the Seamen's Mission, where seafarers from the Philippines and other countries take their daily meals, Schloss der Republik Burj Khalifa OFW I by Jasmin Werner is shown.

At times when the Seamen's Mission Hamburg-Altona — like many other institutions, including Chez Malik's Bar, which also provides a home for our project space Come Over Chez Malik's — must remain closed to visitors, the sculpture can also be seen publicly from the Elbe boardwalk through the windows. Since the work is illuminated by a bright lamp from the inside, it can also be viewed without access to the premises of the Seamen's Mission. Subscribers to the Come Over Chez Malik's newsletter were encouraged and invited to book a room at the Seamen's Mission hotel so that they could see Werner's work on site and support the Seamen's Mission at the same time.

As previously mentioned, Werner's project for Come Over Chez Malik's includes not only Schloss der Republik Burj Khalifa OFW I but also this publication. It functions as an exhibition itself and additionally contains the documentation of Werner's presentation at the Seamen's Mission. Furthermore, it includes the diary-like report by Chris Cadawas, which contributes to the ethnographic scope of the work. Here, the personal and de-anonymized dimension of labor migration becomes tangible. Finally, the publication includes a collection of job offers for Filipino workers published by the Department of Labor and Employment of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration on its official website on November 16th, 2020. The site is the first port of call for global job seekers. The publication will—due to the current situation regarding COVID-19—be sent exclusively by post. A strand of the interwoven story thus spins further and is carried back into the world.